-

Celebrity News1 week ago

Celebrity News1 week agoThe Gayle King-Starring ‘CBS Mornings’ Face All-Time Low Ratings Amid Brutal Cost-Cutting Measures

-

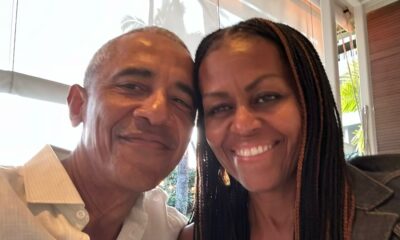

Celebrity News1 week ago

Celebrity News1 week agoBarack & Michelle Obama ‘Barely Even Talked’ During Very Public Dinner Outing in Washington D.C.

-

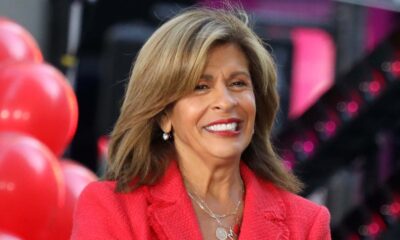

Celebrity News1 week ago

Celebrity News1 week agoHoda Kotb In Talks For Daytime Talk Show, Taking Over Kelly Clarkson’s Spot Following ‘Today’ Exit

-

Celebrity News1 week ago

Celebrity News1 week agoScreen Legend Carol Burnett Showing Tough Love to Troubled Grandson as He Struggles to Stay Afloat

-

Celebrity News1 week ago

Celebrity News1 week agoFormer ‘Good Morning America’ Meteorologist Rob Marciano Struggling to Find Camaraderi at CBS

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoArchaeologist Claims To Have Solved Amelia Earhart Mystery With Stunning Pacific Discovery

-

Celebrity News5 days ago

Celebrity News5 days agoCountry Star Miranda Lambert Wants Husband Brendan McLoughlin To Step Up And Get Back On The Grind

-

Celebrity News1 week ago

Celebrity News1 week agoBruce Willis’ Family Struggles With Fallout as Wife Emma Prepares to Release Personal Memoir on His Dementia Battle

-

Celebrity News1 week ago

Celebrity News1 week agoBruce Springsteen Following Doctor’s Orders as He Embarks on European Tour Amid Health Recovery

-

Celebrity News5 days ago

Celebrity News5 days agoAngelina Jolie’s Exit Strategy Revealed: Why the Oscar Winner Is Eager to Leave Los Angeles for Good

-

Celebrity News1 week ago

Celebrity News1 week agoMatthew McConaughey, Amanda Seyfried, Matt Damon and More A-List Stars Reflect on the Roles that Got Away

-

Celebrity News1 week ago

Celebrity News1 week agoRachael Ray Ghosts Longtime Associates After Fleeing to Italy, Sparks Concern with Unusual Behavior